It’s an amazing story, actually. In the late 1970s, I was hired as a researcher at Canada’s Bell Labs (Bell Northern Research) in Toronto. Our group was trying to figure out how “internetworked computers” used by professionals and managers could change “knowledge work” and the nature of organizations. I got to collaborate with some of the most knowledgeable people in this area in the world at the time, including the great digital pioneer Douglas Engelbart — who invented word processing, the mouse, and hyperlinks (among other things.)

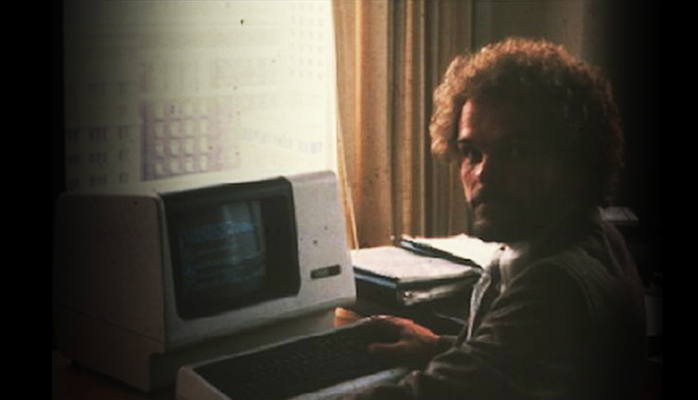

Our group conducted the first-ever controlled experiments about the impact of technology on knowledge work. Half the office worked the old way — with telephones, typing pools, manual calendars, filing cabinets and the corporate library for information. The other half had computers on their desks connected to digital networks. They used a suite of tools that we built for electronic mail, word processing, document co-authoring and management, online information retrieval, personal time management and calendaring, and financial planning tools (spreadsheets had not been invented yet).

I wrote a book about that experience in 1981, but it didn’t sell well. Critics said only programmers would use computers because regular people would never learn to type.

Regardless, I was on the Executive Fast Track. I had received four promotions in two years, and was running the entire division of the company from my massive corner office. Even though our ideas didn’t yet have broad acceptance, I was a rising star in the company and highly regarded as a digital pioneer amongst the global “digerati” of the time.

Which is why it seemed so weird when a colleague named Del Langdon tried to convince me to quit the company and become an entrepreneur. It was circa 1982, in the middle of a brutal recession, and me about to launch a family. And here I had this colleague argue that we should take a dozen people in our division and create a company to help people implement this new class of technology — even though the technology didn’t exist. In fact, when we left the company, the IBM PC had not yet appeared on the market; it would be a full decade before PCs communicated with other technologies in a reasonable manner.

Her advice seemed nuts, but something caused me to listen. With the advantage of hindsight I can reflect on my reasons, unarticulated at the time: we wanted to control our own destiny; we wanted to share in the wealth we created; but most of all, I think we wanted the freedom to try and change the world — to create technology that would transform the way people worked, learned and communicated.

We were partially successful. We consulted to companies and governments, leading some of the earliest implementations of networked workstations in the world. We wrote a book together which had a modest impact. We built a system that eventually was acquired. The IPO didn’t exactly bring us great wealth, but it lead to more good things. Eventually, we lost control of the company. That chapter ended unhappily.

But the legacy was a great one — including that our colleagues all went on to do very interesting work. As for me, I finally wrote a book that someone read — “Paradigm Shift,” in 1992 — as I started to get that “market timing” thing down better. This led to a string of best sellers — “The Digital Economy,” “Growing Up Digital,” “Wikinomics” and a dozen others. It also led to the creation of companies that were significant both in terms of wealth creation and impact in the world.

Today, I feel very fortunate. I am truly the master of my destiny. I have a prosperous and purposeful life beyond my early dreams. In hindsight, the turning point was when I became an entrepreneur.

Today, more and more people will make this choice. Necessity is the mother of invention and good jobs for graduates are scarce. More importantly, the Internet enables small companies to have all the capability of large companies without their main liabilities like legacy building, bureaucracy, culture, and processes. Many will fail, as I did (several times). But for many more, it will be worth it. So consider this my advice to you.